In the eyes of many jurors and reporters, DNA evidence is the modern equivalent of a smoking gun. But as the case of Michael McKinney shows, even the most advanced science can be misleading when used without context.

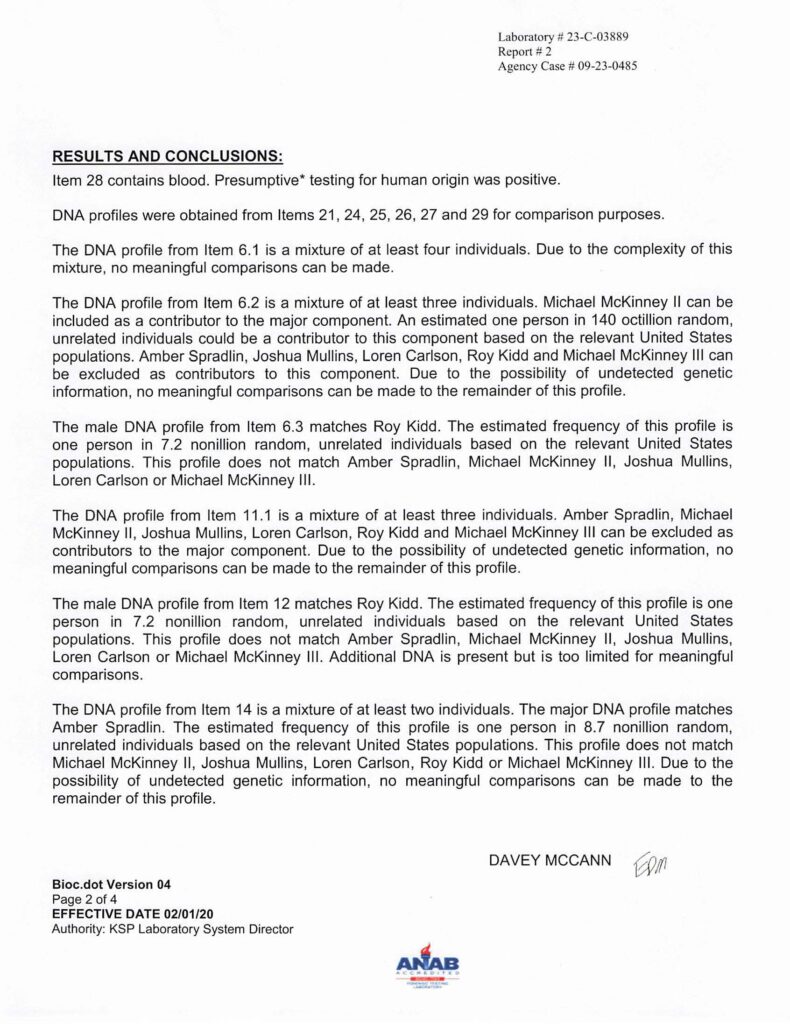

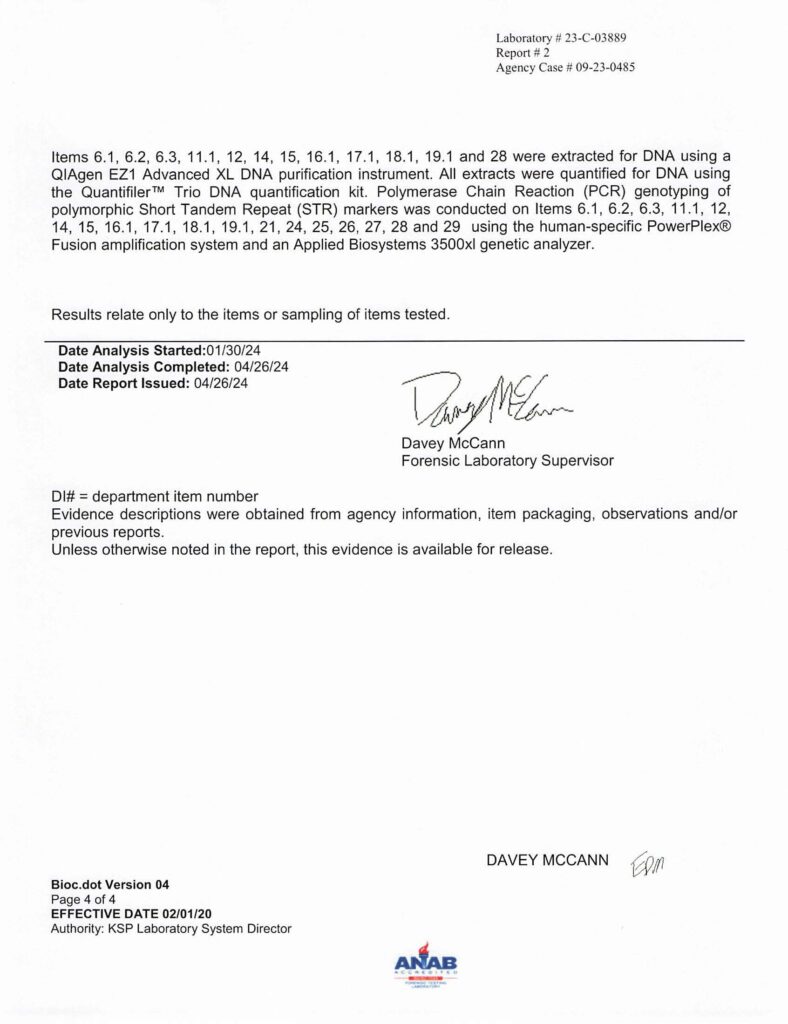

The First DNA Report: Nothing There

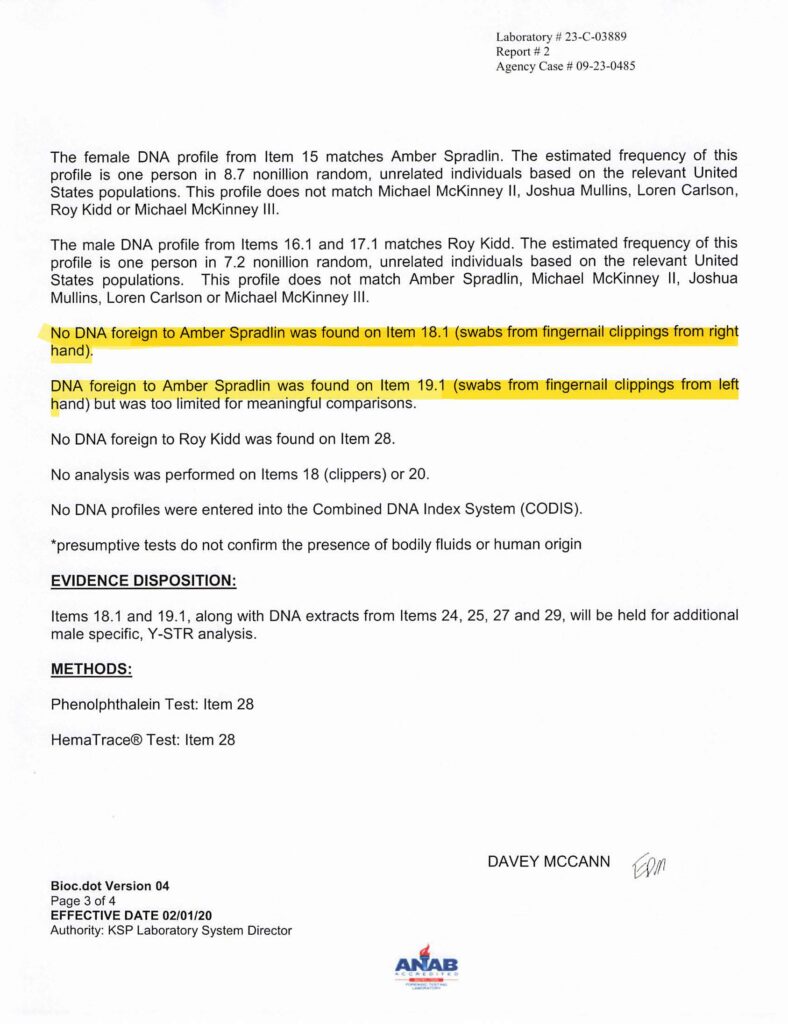

The Kentucky State Police forensic report issued on April 26, 2024, examined the fingernail clippings from the victim, Amber Spradlin. These samples were supposed to hold the truth about what happened. If she had scratched her attacker, the accused’s DNA should have been there.

But the lab found none.

“No DNA foreign to [the victim] was found on the right-hand fingernails.”

“DNA foreign to [the victim] was found on the left-hand fingernails but was too limited for meaningful comparisons.”

In plain terms, that means there was no identifiable DNA from anyone else, including McKinney.

If prosecutors claim the victim fought her attacker and left physical evidence behind, the lab results tell a very different story.

The Second Test: A Weak Signal

When the first round of testing showed nothing useful, investigators ordered a second analysis. This time they used a specialized Y-STR test, which looks for DNA found only on the Y chromosome, present in males.

That second test detected a trace of male DNA.

At first glance, that might sound like a breakthrough. But the science says otherwise. Y-STR testing cannot identify a specific person. It can only show that some male DNA is present. The report itself confirms that it could belong to McKinney, to one of his male relatives, or to an unrelated person entirely.

This type of testing is often used when the original DNA is too degraded or mixed to create a full profile. It is essentially an attempt to pick up a faint signal after the main analysis comes up blank. That faint signal cannot be tied to one person.

“A partial Y-STR result only tells you that a male’s DNA might be there. It cannot tell whose.”

How Secondary Transfer Can Create Confusion

So how did any male DNA end up under the victim’s fingernails if no clear physical struggle occurred? The answer is secondary DNA transfer, one of the most misunderstood phenomena in modern forensic work.

Secondary transfer means DNA can move from one surface or person to another without direct contact. It happens every day in ordinary settings. A handshake, a shared towel, or touching the same doorknob can move microscopic skin cells that contain DNA.

If McKinney and the victim were ever in the same environment, his DNA could easily have been transferred indirectly. Even if they never touched, it could have come from a shared object or another person who acted as an intermediary.

Scientific studies have shown that DNA can survive on surfaces for days or weeks. Researchers have even found DNA from people who never met, simply because they both touched the same items.

That is why secondary transfer has become a growing concern in forensic science. Detecting DNA does not always mean someone was directly involved. This was famously shown in the case of Lukis Anderson, who had spent over a month in jail for a murder charge he was not guilty of, until being exonerated due to proof of secondary DNA transfer.

Why These Results Don’t Hold Up in Court

The language of the report is cautious, and for good reason. When scientists write “too limited for meaningful comparisons,” they are saying there was not enough DNA to make a reliable conclusion. The data was simply too weak.

Y-STR testing introduces even more uncertainty because all males in the same paternal line share the same markers. McKinney’s father, brothers, cousins, and other male relatives would produce identical results.

In forensic science, results this limited are rarely used to draw conclusions, let alone to bring criminal charges.

“I have never seen anyone charged with a crime based on DNA this inconclusive,” said one independent DNA expert who reviewed the findings.

Delays and Doubt

There is growing speculation that the prosecution may be delaying the case because they recognize how fragile their evidence is. Once these reports are presented in court, defense experts will be able to show that the DNA findings have little to no probative value.

Delays in weak cases are not unusual. Sometimes prosecutors stall, hoping new evidence will appear or that the public’s attention will move on. But when a person’s freedom is at stake, every unnecessary delay becomes another injustice.

Justice delayed is still justice denied.

DNA Is Not Infallible

The McKinney case illustrates a larger problem with how DNA evidence is perceived. For years, the public has been taught that DNA never lies. In reality, it is one of the most sensitive and easily misinterpreted forms of evidence there is.

Across the country, there are people who were convicted on partial or mishandled DNA results, only to be exonerated later when retesting showed the evidence was inconclusive or contaminated.

When DNA is used correctly, it can reveal the truth. When it is stretched to fit a narrative, it can destroy lives.

What the Public Needs to Understand

The public deserves the full picture. The first lab test found no foreign DNA at all. The second, far weaker test found a small trace of male DNA that cannot be linked to any one person.

That is not proof of guilt. It is a reminder that the science here is uncertain and should be treated with caution.

If the justice system is to remain fair, then McKinney deserves what every defendant deserves: the presumption of innocence until proven guilty.

A partial, inconclusive trace of DNA should never be used to fill in the blanks of an investigation.

What Is Secondary DNA Transfer?

Secondary DNA transfer happens when someone’s DNA moves from one place or person to another without direct contact.

For example, if Person A shakes hands with Person B, and Person B later touches a surface, Person A’s DNA can end up there too.

It can happen through shared objects like towels, phones, doorknobs, or clothing. Even a light brush of fabric can move enough cells for a forensic lab to detect.

This is why finding someone’s DNA does not automatically mean they were present during a crime or had contact with the victim.

DNA evidence tells us that genetic material was found. It does not always tell us how it got there.

The forensic record in this case is clear. The DNA results are not proof. They are noise.

In the hands of a responsible court, that should not be enough to convict anyone.

Michael McKinney’s case deserves not just scrutiny, but fairness. Until there is real, reliable evidence, the only conclusion we can draw from the science is uncertainty, and uncertainty should never send a person to prison.