A New York appellate panel has unanimously thrown out the 2022 conviction of Shawn Exford, ruling that the trial judge’s failure to give a required circumstantial evidence instruction deprived jurors of essential guidance in a case resting entirely on inference.

The decision, issued in mid-2025, reverses a verdict that sent Exford to prison for murder and arson after a fatal apartment fire. The opinion is brief but pointed: when every step of proof requires assumption rather than direct observation, jurors must be instructed on how to weigh uncertainty.

A Fire, a Shadow, and a Theory

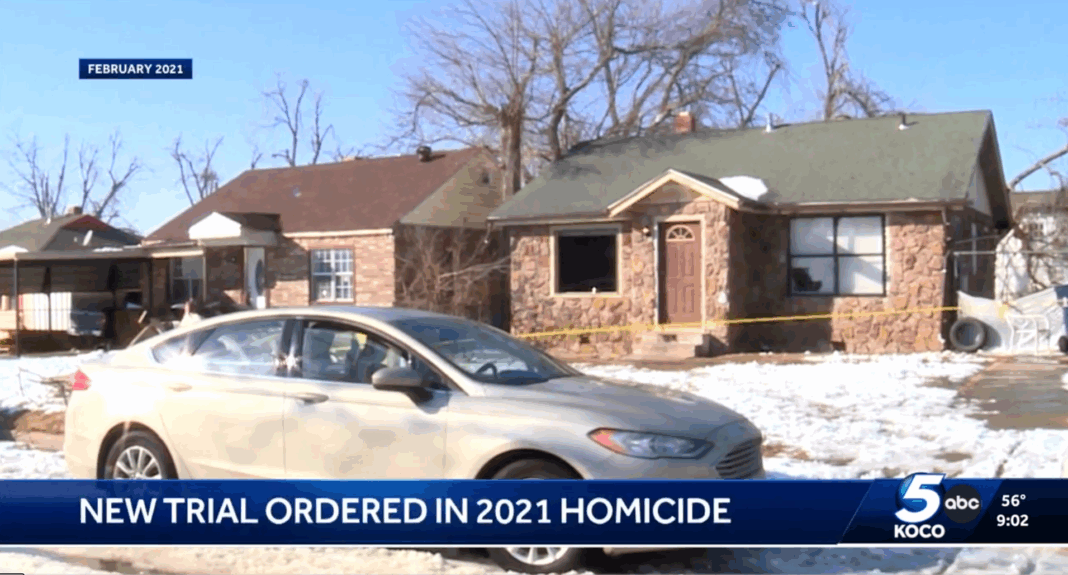

The blaze that killed one resident and injured others tore through a Bronx apartment building late one winter night. Investigators identified Exford, a tenant in the complex, as the last person seen leaving the entryway before flames erupted.

The prosecution’s entire case turned on a short segment of surveillance video. The footage, grainy and distant, showed what looked like a faint glow in the doorway as Exford walked out and disappeared down the street. There were no eyewitnesses, no accelerants found on his clothing, no confession, and no physical trace linking him to an ignition source.

A fire investigator testified that he had ruled out accidental causes and concluded the blaze was intentionally set. With that expert opinion and the brief video, prosecutors argued the circumstantial chain was complete: Exford was there, the fire started, and therefore he must have lit it.

The Instruction That Was Never Given

New York law treats circumstantial evidence with measured caution. When a case depends solely on inference, judges must tell jurors that they may convict only if the evidence excludes, “to a moral certainty,” every reasonable hypothesis consistent with innocence.

That instruction—often decisive in close cases—was never given. Defense attorneys requested it. The trial judge declined, saying the evidence was mixed, not purely circumstantial. The jury convicted after brief deliberations.

The appellate court’s opinion dismantled that reasoning. It found that all proof of guilt required logical steps, not direct observation, and that the omission of the instruction could not be dismissed as harmless error. The panel concluded that jurors were never told how to distinguish a possibility from a certainty—a failure that went to the heart of the verdict’s reliability.

Reading the Ruling Plainly

The court’s message was clear: when every conclusion depends on inference, procedure becomes substance. Without the proper instruction, the standard of proof itself risks dilution.

One former prosecutor described the decision as “a reminder that even a strong narrative can’t replace the evidentiary bridge you have to build.” Another defense attorney called it “a textbook example of how courts safeguard the presumption of innocence when physical proof is missing.”

The appellate judges stopped short of criticizing the prosecution’s good faith, but their language was unmistakable—this was not a technical reversal, but a substantive one.

How Inference Can Overreach

Arson cases often hinge on expert reconstruction and circumstantial detail. Flames erase evidence; smoke clouds intent. In that vacuum, investigators lean on patterns, timing, and human behavior. Yet those elements can easily become over-interpreted.

Exford’s jury saw a blurry video that showed a flicker of light—perhaps a flame, perhaps reflection—and heard an expert say that only arson could explain the fire. From those pieces, guilt was inferred. What the appellate court restored was not exoneration but balance: the reminder that inference must be disciplined by law, not impulse.

Structural Pressures Behind the Error

The case also reflects pressures that frequently distort fact-finding in high-profile tragedies. Jurors, confronted with death and destruction, feel a collective pull toward resolution. Investigators and prosecutors face public expectation to produce answers. And when evidence is ambiguous, experts can become inadvertent narrators, translating uncertainty into conviction.

Legal scholars note that such cases expose a quiet form of systemic bias: the belief that every tragedy must have an identifiable cause and an individual to blame. The circumstantial evidence charge exists precisely to counter that human tendency—to remind jurors that plausible does not mean proven.

What Comes Next

The Bronx District Attorney’s Office has not announced whether it will retry Exford. It may choose to present the same evidence with the proper instruction, reassess the charges, or negotiate a resolution short of trial.

If a retrial proceeds, the defense is expected to challenge the strength of the video and the limits of fire-science testimony, emphasizing alternative explanations such as electrical malfunction or post-ignition spread. Prosecutors, meanwhile, must persuade jurors not only that the fire was arson, but that Exford alone set it—without a single eyewitness or confession.

A Broader Reflection on Fairness

The Exford reversal highlights a truth easily lost in modern trial culture: precision in process is not a procedural nicety but a guardrail against error. Jurors must know how to handle the invisible gaps between fact and inference. When they are left without that framework, verdicts risk being driven by instinct instead of evidence.

This decision restores not only a defendant’s right to a fair trial but a community’s faith that the justice system can pause before drawing conclusions from smoke and shadow. Whether Exford is retried or ultimately cleared, the case has already reaffirmed a vital principle—that certainty must be earned, not assumed.